Federici, on the other hand, insists these transitions were part of a larger capitalist project of alienation that continues today.A resource shared for educational and research purposes. Even many socialists narrate the Enclosures and the displacement of peoples as a moment of progress, or, if critical, still present it as a necessary transition.

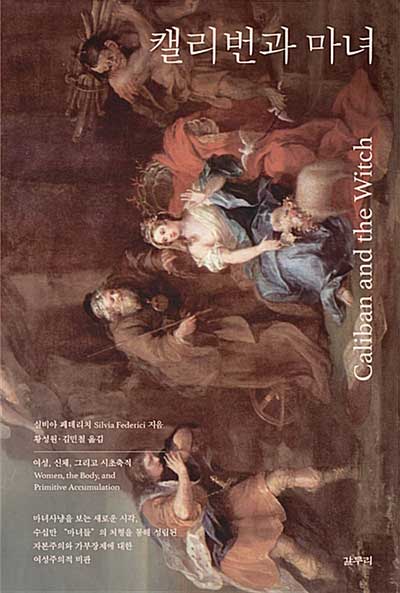

Usually, the transition from pre-capitalist social arrangements to capitalist ones is presented as an act of progress, a “liberation” of primitive peasants from life on the land into the enlightenment of urban subjectivity. That’s why Silvia Federici’s Caliban & The Witch is so important. The de-growth movement, eco-feminism, indigenous resistance groups such as the Zapatistas, land-access struggles and anti-development movements-especially in the Global South-are all part of this tendency, and so am I. Rather than constantly proposing future technologies that might one day save us from capitalist exploitation and environmental collapse, it insists that the way of fighting capitalism is recovering and reclaiming our humanity, our connection to body and land, and our older forms of social and economic life. The second kind of leftism, on the other hand, is highly critical of capitalist technology and the deep alienation that capitalism creates. The DSA, Jacobin, “solarpunk” anarchists, much of the Antifa hierarchy, the “left-wing” of the Democratic Party, and transhumanists and “family-abolitionists” like Sophie Lewis are all part of this tendency.

This is the kind of “leftism” most common in the United States and the United Kingdom, and is very often identitarian. There are really two ways of thinking about modern capitalist life within “leftism.” The first, which is what we might call techno-utopianism or utopian socialism, embraces all the disruptive technological “advances” of capitalism while imagining that we can just re-arrange society so that everyone benefits equally from it.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)